For many foreign investors considering Indonesia, one number has long loomed large: IDR 10 billion. It is often cited—sometimes asserted—as the minimum capital required to establish a foreign-owned company (PT PMA). For smaller firms, service providers, and first-time entrants, the figure has acted as a psychological barrier, deterring exploration before conversations even begin.

In 2025, Indonesia’s regulatory framework has clarified a distinction that was always present but rarely understood. The IDR 10 billion figure is not, in most cases, the cost of entry. It is more accurately the cost of growth—a benchmark tied to investment scale rather than the cash that must be injected on day one. Understanding this difference is increasingly central to how foreign investors plan market entry and execution.

The origin of the IDR 10 billion assumption lies in historical policy and practice. For years, PT PMA companies were commonly categorized as “large enterprises,” a label often associated with investments exceeding IDR 10 billion. Older guidance materials and consultant briefings reinforced this interpretation, and earlier licensing systems did little to separate capital concepts clearly.

Over time, “capital,” “investment value,” and “funds required” became interchangeable in everyday use—even though they are legally distinct. The result was a simple, but misleading, takeaway: to start a PT PMA, you must deposit IDR 10 billion upfront.

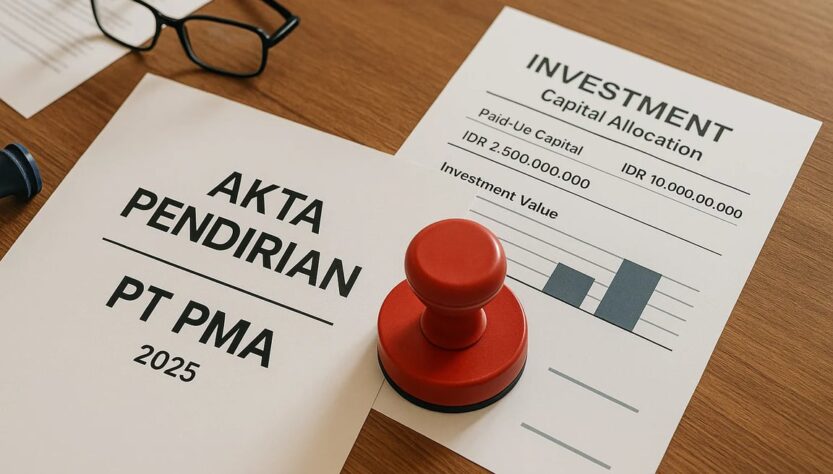

Indonesia’s more recent investment regulations, implemented alongside the risk-based licensing system (OSS RBA), have drawn a sharper line between paid-up capital and investment value. Under the current framework, the minimum paid-up capital for most PT PMA establishments is IDR 2.5 billion. This is the amount shareholders are required to actually inject into the company’s bank account at establishment and retain for a defined period.

The IDR 10 billion figure has not disappeared. Instead, it typically applies to planned investment value—the projected scale of spending over time on operations, equipment, staffing, and development, excluding land and buildings. In other words, it describes the size of the business Indonesia expects to see as it grows, not the cash threshold for opening the door.

Paid-up capital functions as the company’s initial financial base. It supports early operations, signals seriousness to regulators and banks, and underpins credibility. For many service-oriented businesses—consulting, technology, trading, or creative services—IDR 2.5 billion is sufficient to meet this requirement at entry.

Investment value, by contrast, reflects ambition and trajectory. Authorities use it to assess whether a business fits within certain classifications and risk categories. For many KBLI codes, particularly beyond micro or small-scale activities, the expected investment value still exceeds IDR 10 billion over the life of the project.

Seen this way, the distinction becomes clearer: IDR 2.5 billion enables entry; IDR 10 billion often defines scale.

Indonesia’s shift to the Online Single Submission Risk-Based Approach has reinforced this logic. Instead of imposing a uniform capital threshold, OSS RBA evaluates businesses based on sector, activity, and risk profile. Capital expectations are aligned more closely with operational reality.

This has practical consequences. Lean, service-based foreign businesses can enter the market with realistic capital structures, provided their investment plans are coherent and compliant with the chosen business classification. The system rewards precision rather than overcapitalization.

The clarified framework does not mean all sectors are equally accessible. Capital-intensive industries—manufacturing, energy, natural resources, large-scale logistics, and certain construction segments—still face higher thresholds through sector-specific regulations or licensing conditions.

In these cases, IDR 10 billion or more may indeed be relevant early on. The key variable is not nationality, but industry profile. Choosing the correct business classification (KBLI) is therefore central to determining whether IDR 2.5 billion is adequate at entry or whether higher commitments are unavoidable.

Despite regulatory clarity, confusion continues for two reasons. First, many investors still encounter outdated advice that fails to separate paid-up capital from investment value. Second, misalignment between declared figures and actual deposits can trigger delays under OSS RBA, reinforcing the perception that higher capital is always required.

In practice, the issue is less about how much investors plan to spend over time and more about whether declarations, deposits, and licensing data are consistent.

For foreign investors, capital planning is increasingly a strategic exercise. Paid-up capital affects operational flexibility and banking relationships. Investment value shapes licensing scope and future expansion. Treating them as interchangeable can lead to either unnecessary capital lock-up or regulatory friction.

This is why many investors seek guidance on company registration and capital structuring before committing funds. Firms such as CPT Corporate are often referenced by investors navigating this distinction—helping align paid-up capital, investment plans, KBLI classification, and OSS RBA requirements so entry is both compliant and efficient.

Reframing IDR 10 billion as a cost of growth rather than a cost of entry lowers the perceived barrier to Indonesia’s market, particularly for service and technology businesses. It also signals Indonesia’s intent to attract a broader spectrum of foreign capital—without abandoning expectations around scale, credibility, and compliance.

The takeaway is not that Indonesia has made entry “cheap,” but that it has made the rules clearer. Investors who understand where capital is required—and why—can enter the market faster and with greater confidence.

Indonesia’s evolving investment framework replaces myth with definition. IDR 10 billion was never a universal entry fee; it was a proxy for scale that became misunderstood over time. In 2025, the distinction is explicit.

For foreign investors, the question is no longer whether IDR 10 billion is required to enter Indonesia, but when and how capital should be deployed as the business grows. Those who answer that question early are better positioned to move from interest to execution—without letting outdated assumptions dictate their strategy.

This press release has also been published on VRITIMES