Sustainability on a compact island means designing flows so that one sector’s by‑products become another’s feedstock. Nowhere is this clearer than in the nexus of food, waste, and energy.

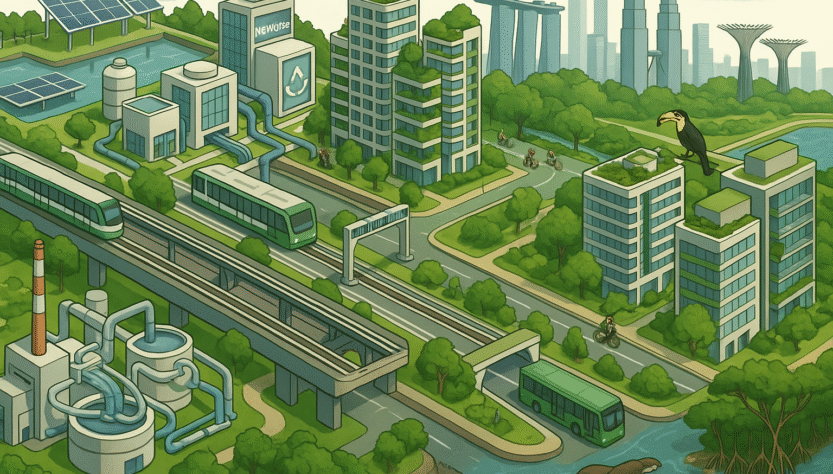

Urban agriculture is rising, not as a romantic ideal but as supply chain insurance. Rooftop farms, vertical systems in warehouses, and high‑tech greenhouses produce leafy greens and herbs close to consumers. These systems recirculate water and precisely meter nutrients, drastically cutting inputs per kilogram. Cold chain logistics are shorter, reducing spoilage and emissions from transport.

Downstream, the city tackles organic waste with source segregation pilots in housing estates and commercial kitchens. Clean organics flow to anaerobic digesters—often co‑located with wastewater plants—where microbes convert them into biogas. The gas spins turbines or feeds boilers, and the digestate can be further processed for soil amendments. Food that is still edible is rescued through redistribution networks, attacking waste at the top of the hierarchy.

Packaging and e‑waste policies push producers to design for recycling and fund collection systems. Materials recovery facilities sort streams more effectively when contamination is low, and digital tracking improves accountability. Incineration remains part of the mix to shrink residual volumes and recover energy, buying time for the offshore Semakau Landfill.

Energy ties the loop together. Waste‑to‑energy plants export electricity; heat is captured for on‑site processes; and grid‑interactive buildings smooth demand to integrate more solar. By co‑locating facilities—water reclamation, waste processing, and power generation—Singapore strips out duplicated infrastructure and reduces truck movements on crowded roads.

These loops are not perfect circles; leakage exists. But each turn reduces imports, stretches infrastructure life, and makes the urban metabolism more resilient to shocks. On a small island, that resilience is the real harvest.